Difference between revisions of "Internet anonymity"

Paul Herring (talk | contribs) |

Paul Herring (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

Nearly every week, if not every day, certainly in the United Kingdom, there are calls from one group of people or another for a ban on what is considered '[[internet anonymity]].' | Nearly every week, if not every day, certainly in the United Kingdom, there are calls from one group of people or another for a ban on what is considered '[[internet anonymity]].' | ||

| − | The fact that, for the vast majority of people who use the internet, anonymity on the internet is a very high bar to achieve, what most of these calls are for is for people to be instantly recognisable whenever they produce content on the internet, be it a MediaWiki site such as this or Wikipedia, to the comments section beneath any news story on your local paper's website. | + | The fact that, for the vast majority of people who use the internet, anonymity on the internet is a very high bar to achieve, what most of these calls are for is for people to be instantly recognisable whenever they produce content on the internet, be it a MediaWiki site such as this or Wikipedia, to the comments section beneath any news story on your local paper's website; it's just very difficult, for the normal person, to verify that a particular comment was made by a particular person. |

| + | |||

| + | Those fighting for the removal of '[[internet anonymity]]' want everyone on the internet to be able to tell who everyone else is easily. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Those defending '[[internet anonymity]]' want to be able to post 'anonymously' without fear of retribution from, for example, their employers - regardless of whether what they're saying has anything to do with their employers. Or their neighbours (again - regardless of whether it has anything to do with them or not.) | ||

| + | |||

| + | Just because there are people who feel the need to advertise themselves publicly on Facebook, for example, including their every ([http://www.facebook.com/pages/Bowel-movements/26129312317 bowel]) movement, that does not mean that everyone is willing to give up their right not to be (easily) identified by their real-life peers on the internet. They want their privacy, and moves to remove '[[internet anonymity]]' attempt to remove that privacy. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{quote|Commentators often attempt to refute the nothing-to-hide argument by pointing to things people want to hide. But the problem with the nothing-to-hide argument is the underlying assumption that privacy is about hiding bad things. By accepting this assumption, we concede far too much ground and invite an unproductive discussion about information that people would very likely want to hide. As the computer-security specialist Schneier aptly notes, the nothing-to-hide argument stems from a faulty "premise that privacy is about hiding a wrong." Surveillance, for example, can inhibit such lawful activities as free speech, free association, and other First Amendment rights essential for democracy. <ref>[http://chronicle.com/article/Why-Privacy-Matters-Even-if/127461/ Why Privacy Matters Even if You Have 'Nothing to Hide'] - The Chronicle of Higher Education - Washington DC</ref>}} | ||

| + | |||

== Anonymity? == | == Anonymity? == | ||

Revision as of 20:23, 26 September 2012

Nearly every week, if not every day, certainly in the United Kingdom, there are calls from one group of people or another for a ban on what is considered 'internet anonymity.'

The fact that, for the vast majority of people who use the internet, anonymity on the internet is a very high bar to achieve, what most of these calls are for is for people to be instantly recognisable whenever they produce content on the internet, be it a MediaWiki site such as this or Wikipedia, to the comments section beneath any news story on your local paper's website; it's just very difficult, for the normal person, to verify that a particular comment was made by a particular person.

Those fighting for the removal of 'internet anonymity' want everyone on the internet to be able to tell who everyone else is easily.

Those defending 'internet anonymity' want to be able to post 'anonymously' without fear of retribution from, for example, their employers - regardless of whether what they're saying has anything to do with their employers. Or their neighbours (again - regardless of whether it has anything to do with them or not.)

Just because there are people who feel the need to advertise themselves publicly on Facebook, for example, including their every (bowel) movement, that does not mean that everyone is willing to give up their right not to be (easily) identified by their real-life peers on the internet. They want their privacy, and moves to remove 'internet anonymity' attempt to remove that privacy.

Commentators often attempt to refute the nothing-to-hide argument by pointing to things people want to hide. But the problem with the nothing-to-hide argument is the underlying assumption that privacy is about hiding bad things. By accepting this assumption, we concede far too much ground and invite an unproductive discussion about information that people would very likely want to hide. As the computer-security specialist Schneier aptly notes, the nothing-to-hide argument stems from a faulty "premise that privacy is about hiding a wrong." Surveillance, for example, can inhibit such lawful activities as free speech, free association, and other First Amendment rights essential for democracy. [1]

Anonymity?

IP Addresses

In reality, it is very difficult to be totally anonymous on the internet.

Every time you access a web page, you leave behind a record of which ISP you are using via your IP address in that sites logs.

Whether the general public can obtain that data is up to the site, but in general it's not something that's immediately accessible to someone who isn't actually involved with the site.

For example, on most MediaWiki sites, if you aren't logged in, any changes you make are recorded against your IP address. On the Revision History page of Wikipedia's Anonymity article taken on the evening of 26 Sep 2012 we have:

(cur | prev) 00:27, 9 June 2012 Trident13 (talk | contribs) . . (18,241 bytes) (+25) . . (→See also: * Anonymous blogging) (undo)

(cur | prev) 20:32, 18 May 2012 Adjwilley (talk | contribs) . . (18,216 bytes) (-2) . . (Good faith revert of edit(s) by 198.189.235.79 using STiki all caps) (undo)

(cur | prev) 20:28, 18 May 2012 198.189.235.79 (talk) . . (18,218 bytes) (+2) . . (→Mathematics of anonymity) (undo)

(cur | prev) 20:28, 18 May 2012 198.189.235.79 (talk) . . (18,216 bytes) (0) . . (undo)

(cur | prev) 05:40, 25 March 2012 Wiki141592 (talk | contribs) . . (18,216 bytes) (-372) . . (removed 'trend' statement; 2009 quote with no citation; and minor edits) (undo)[2]Shown with a darker background, we have two entries by 'username' 192.189.235.79 - this is an 'anonymous' user who edited the page.

Asking one of the numerous services on the internet dedicated to such things, if you put http://whois.arin.net/rest/nets;q=192.189.235.79?showDetails=true&showARIN=false&ext=netref2 into your browser you'll find that the company that owns that IP address (along with 255 others in this particular part of the address space) is Center for Naval Analyses.

With that information, if you want to know who made those edits, then you simply contact the CNA, and ask them "who, at 20:28 on the 18th May 2012, had 198.189.235.79 as their IP address."

Problems with IP addresses

Naturally the CNA could tell you to bugger off; and if the ISP concerned was a large one - like Verizon in the states - getting this information out requires slightly more than just a request; a warrant at the absolute minimum would typically be needed.

Additionally the authority responsible for the IP address concerned might not keep records (likely for CNA,) or they may not keep them long enough. But the theory is there - if you have an IP address and a time, it gives you sufficient information to at least get you close, if not at, the person concerned.

Unless, of course, the IP address is the single public address for a company, or a household. If you have wireless in your house, and you have more than one computer accessing the internet, then all your devices will have (to the websites they visit) exactly the same IP address. But then asking Verizon who had an IP address at a particular date still gives you the household that visited the site, and deciding who's responsible for behaviour in that household is a favourite topic of companies like the RIAA.

With companies with all their employees behind the same, the process of discovery is usually a bit trickier, but ultimately (depending on that company's own logs) it can be done; supplying them with (e.g.) an additional URL they can use to search their logs will usually allow them to find who, internally, was (ab)using a site. (Most companies record what their employees are doing on the internet. Generally no-one actually looks at them without reason, but they are recorded.)

Nicknames/Nom-de-plumes

Most private commentators on the internet tend to pick a 'handle' and try to stick to it on every forum/blog/website that uses usernames. Some of these names enter the public conciousness as 'real names,' such as when the Tobacco Tactics website wrote a page on Dick Puddlecote and stated, without apparent irony, that

..Puddlecote says he runs his own transport business, yet there is no "Puddlecote" listed as a Director at Companies House. [3]

Seriously, though, most times when you see a distinctive name you recognise somewhere on the internet, it will one of three possibilities:

- the person you think it is, using the same name elsewhere

- a completely different person who thought of the same name or

- someone trying to impersonate one of the above two

.. and generally, you can generally tell which of them it is. Most people are happy with this situation, and feel that the voluntary nature of it lacks the bully-stateism seen evidenced elsewhere on this website.

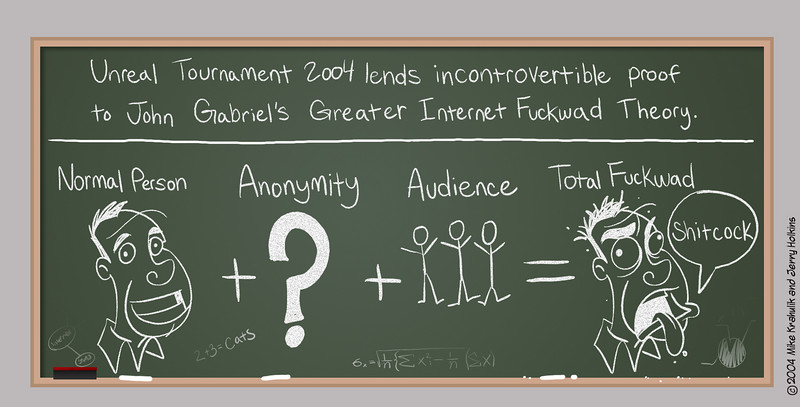

Where this falls down, of course, is the sites that don't force such usernames tend to bring out the people who exhibit what Wikipedia calls Online Disinhibition Effect, or as most on the internet know it 'John Gabriel's "Greater Internet Fuckwad Theory"' illustrated by this Penny Arcade comic back from 2004:

And as with minimum pricing, the solutions generally proposed inconvenience, annoy, and evoke a whole range of other negative emotions in the vast majority of the population (who care about such things) who aren't the problem, to try and fix the problem with the small minority, without actual evidence that the proposal will actually fix the problem with the small minority.

References

- ↑ Why Privacy Matters Even if You Have 'Nothing to Hide' - The Chronicle of Higher Education - Washington DC

- ↑ Revision History of Anonymity from Wikipedia - WebCitation taken 26 Sep 2012

- ↑ WebCite taken on 26th Nov 2012 of Dick Puddlecote - Tobacco Tactics