Standardised packaging

Plain packaging is intended, according the the anti-smoking proponents, to reduce the number of people (some claims state 'children,' instead of people) taking up smoking because it will "make them less attractive."

Others have pointed out that plain packaging lowers the existing barriers to counterfeiting by allowing the counterfeiters to not bother too hard with one aspect of making fake cigarrettes.

J Padilla & N Watson (2008)

Commissioned for Phillip Morris International (PMI), by The Law and Economics Consulting Group(LECG) to review previous research on the subject of generic (plain) packaging, largely with regard to teenagers. It concludes that none of those papers reviewed could provide a reliable basis on which to determine if plain packaging would reduce smoking levels.

M Goldberg, et al. (1995)

When Packages Can't Speak: Possible Impacts of Plain and Generic Packaging of Tobacco Products was a 1995 report based on a series of surveys, for Health Canada, of teenagers, over 5 different studies, to examine the potential effect plain packaging might have on

- the uptake of smoking to begin with,

- the impact on the recognition of, and the ability to remember, the warnings on packaging,

- the probability of stopping smoking

For the Direct Questioning surveys, Padilla and Watson(2008) summarised that

- Teenagers have mixed views on what they believe to be the impact of generic [plain] packaging.

- Results suggest that the effects of generic [plain] packaging on smoking would be marginal.

In the Visual Image survey that

- Generic packaging increased the recall rate of only one of three health warnings. The authors suggest that the exposure time was too short and that these results cannot be extrapolated to a more natural long term-setting.

And in the Conjoint survey that

- Packaging is generally as important as brand influence and peer influences (except for teenage non-smokers).

- Results suggest that plain and generic packaging will, to some “unknown degree, encourage non-smokers not to start smoking and smokers to stop smoking”

National Survey

The purpose of the National Survey was to assess the knowledge, attitudes and beliefs held by teenagers (14-17 years) regarding smoking, brands, brand images, generic packaging and perceived impact of such packaging on teenagers. From an initial pool of 6,213 teenagers, 1,200 were eventually questioned from 14 Canadian cities. Those not eventually questioned dropped out because they didn't fit the age criteria, they were overt anti-smokers, or they simply refused to answer the questionairre.

Padilla & Watson(2008) concluded that

- The objective of the survey was simply to provide descriptive statistics on smoking beliefs, patterns and behaviours of teens in Canada. No attempt was made to establish a causal relationship between cigarette packaging and youth smoking.[Page 40]

Word Image Survey

The purpose of this survey was to determine what, if any, differences were perceived between branded packets, plain packets or packets with a "lungs" symbol. The cohort for this study seems to have been the same cohort as the National Survey, since 1,200 took part, and they answered the same screening questions.

Padilla & Watson(2008) concluded that

- The results of this survey cannot be used to inform a policy decision regarding implementation of generic packaging. The likely effects of generic packaging can only be inferred from a comparison of the situation before and after the measure.[Page 42]

Visual Image Survey

Pictures of 6 (types of) people were shown with different package types (3 brands, and pack types of branded, plain or plain+"lungs",) in the lower right hand corner. Participants were then asked to agree/disagree on a 5 point scale with the statement “Consider this (picture). Is (brand name) in this package right or wrong for this (woman/man)”. The brands selected were from a previous survey for which teenagers had the greatest convergant images.

Padilla & Watson(2008) again:

- By selecting only those brands that were more strongly associated with a certain person-type in the national survey, the results of this analysis may have overestimated the actual link between brands and perceived images.[Page 43]

Recall and Recognition Survey

This survey was of 400 Vancouver teenage smokers, to assess what differences plain/branded packs had on how much attention was paid to both the brand, and any warning messages present on the packs.

3 images of a table with a packet of cigarrettes, different brand each time, (with the pack either always branded or always plain), a magazine, can of pop and a bottle of headache pills. Images were shown for 4 seconds, and the respondants asked to list what they could see, the brand of cigarettes, and the warning on the packet.

The respondants were then shown all three packs with the warnings hidden, and asked to name which warning went on which pack.

Padilla & Watson(2008):

- The results of the study do not indicate that health warnings are better recalled when displayed on generic packages.

Conjoint survey

Respondants, which was the same cohort that participated in the Recall and Recognition survey above, were asked to choose between alternatives that differed in

- package type,

- brand,

- price, and

- peer influence (friends smoke/do not smoke).

Goldberg et al (1995) themselves concluded the extent of the influence of generic packaging on smoking decisions:

- cannot be validly determined by research that is dependent on asking questions about what they think or what they might do if all cigarettes sold in the same generic packages.[Page 129]

Department of Health(2008)

In 2008 the UK DoH commissioned a consultation with the results published in a report titled Consultation on The Future of Tobacco Control[1]. In it, it reported (with emphasis added):

- Research shows that this may reduce the attractiveness of cigarettes and further ‘denormalise’ the use of tobacco products. Studies show that plain packaging reduces the brand appeal of tobacco products, especially among youth, with nearly half of all teenagers believing that plain packaging would result in fewer teenagers starting smoking.[Page 7]

However, later on it goes on to say

- 3.65 The Department of Health is not aware of any precedent of legislation in any jurisdiction requiring plain packaging of tobacco products.[Page 40]

So there is no research in to what effects, if any, plain packaging elsewhere may have.

- 3.66 Studies show that plain packaging reduces the brand appeal of tobacco products, especially

among youth. A Canadian study reveals that virtually all 14–17 year olds involved in the

study said that the reason they might start smoking or currently do smoke is to be ‘cool’ or to

‘fit in’. [Page 40]

This is referencing M Goldberg, et al. (1995) which is not a reliable guide as to what effect plain packaging will have.

- 3.67 The same study also found that: [Page 40]

M Goldberg, et al. (1995) again.

- 3.69 Plain packaging may also increase the salience of health warnings. Studies show that students

have enhanced ability to recall health warnings on plain packs.[Page 40. My emphasis.]

Or it might not. If they're going to insist on referencing M Goldberg, et al. (1995) for two paragrahs then I'd draw attention to the results of their Recall and and Recognition survey where it was explicitly not shown that plain packaging enables better recall of health warnings.

- 3.75 As there are no jurisdictions where plain packaging of tobacco products is required, the research evidence into this initiative is speculative, relying on asking people what they might do in a certain situation. The assumption is that changes in the packaging will lead to changes in behaviour. [Page 41. My emphasis]

Indeed it is, though Australia may provide some light on the subject very soon.

- 3.76 Plain packaging may force tobacco companies to compete on price alone, resulting in cigarettes becoming cheaper. However, if a decrease in price were to follow the introduction of plain packaging, increases in tax on tobacco could counter the effect.

Unintended consequences? And as if there wasn't enough tax on the product in the UK to begin with. The Laffer Curve never seems to bother the government when it comes to taxes for some reason.

3.77 Children may be encouraged to take up smoking if plain packages were introduced, as it could be seen as rebellious. However, the Department of Health is not aware of any research evidence that supports such concerns.

They clearly aren't looking hard enough for teenage rebellion being a cause for taking up smoking:

Ethnic and gender differences in risk factors for smoking onset: Robinson, Leslie A.;Klesges, Robert C. (1997)

- In a number of studies, rebellious children have been found to be significantly more likely to smoke

Smoking in Children and Adolescents: R Evans et al. (1979)

- The third section reports findings of studies focusing on several psychosocial factors influencing the decision to smoke: [...], siblings who smoke, rebellion against family authority, [...], and perceptions of the dangers of smoking.

Predictors of smoking intentions and smoking status among nonsmoking and smoking adolescents, Vida L. Tyc, Hadley, et al.(2004)

- Results: Parental smoking, higher perceived instrumental value, higher risk taking/rebelliousness, higher perceived vulnerability, and older age increased the odds of an adolescent being a smoker.

So it's clearly been researched, and in some cases found to have a possitive correlation with smoking. Not that's it's terribly easy to find this sort of thing these days.

Back to the consultation:

- 3.79 Some stakeholders have suggested that plain packaging may exacerbate the illicit tobacco market, as it could be easier for counterfeit producers to replicate the plain packages than current tobacco packaging. ...

Well not having to have 100's of different brands to reproduce, and having them replaced by different lettering in the same font, may go some way to reducing the outlay required for (new) forgers to setup may go some way to exaserbate this problem...

- ... A way to counteract this potential problem would be to require other sophisticated markings on the plain packages that would make the packages more difficult to reproduce. ...

Since they don't suggest in detail what this might entail, I suggest that anything they can come up with will be not be difficult for the forgers of current packs. If it can be printed on the packs by the manufacturers then the forgers can do the same. If it's, for example, an external label produced by the likes of De La Rue, then all the forgers have to do is find someway to steal some from somewhere.

- ... In addition, the colour picture warnings, which must appear on all tobacco products manufactured from October 2008, would remain complicated to reproduce.

They're doing it now. They can't be that complicated.

- 3.80 If plain packaging was to be introduced, it could be more difficult for retailers to conduct inventory checks, and customer service could be made more difficult at point of sale. However, brands could be stacked in alphabetical order, for example, to facilitate quick identification, [...]

Well, since everything will soon be hidden behind shutters in the UK, and they're not working with branded packs, it's certainly not going to be easier with plain ones.

- 3.81 The introduction of plain packaging for tobacco products may set a precedent for the plain packaging of other consumer products that may be damaging to health, such as fast food or alcohol. Nonetheless, as tobacco is a uniquely dangerous and extremely widely available consumer product, it has for some time merited different regulatory and legislative treatment from other consumer products.

But the unstated problem here, is that the 'ban tobacco' model is being used elsewhere, and mission creep is already occuring in the areas of fast food and alcohol.

The 'University of Bristol' Study

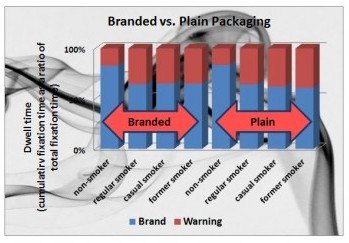

One citation for this claim is the study entitled Plain packaging increases visual attention to health warnings on cigarette packs in non-smokers and weekly smokers but not daily smokers by Marcus R. Munafò, Nicole Roberts, Linda Bauld & Ute Leonards. The title of the study pretty much sums up the findings of the study which basically involved studying the (dominant) eye movements of 15 non-smokers (never smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their life), 14 'weekly' smokers (at least one per week, but not daily) and 14 daily smokers (at least one per day.)

Specifically, they measured how long people looked at the warning messages on both plain and branded packs, and the difference in amount of time between the types of packs and the types of smokers.

Participants were instructed that they'd be shown some images in the first phase of the experiment, and would have to indicate whether or not any images presented in the second phase were present in the first.

The first phase consisted of (randomly) 10 images of plain packs and 10 images of branded packs with 10 warnings (one per type of pack) present and each image was shown for 10 seconds.

The second phase, was 10 images from phase 1, and 10 new images (with each set of 10 having 5 plain and 5 branded packs, and 5 warnings,) and the participants given 5 seconds per image to decide if it was present in phase 1 or not.

Eye movements were tracked in only the first phase.

As summarised by the study's titile, they found that the non- and weekly- smokers tended to look at the warning more if the pack was plain than if it was branded.

Problems with the Bristol Study

The images used

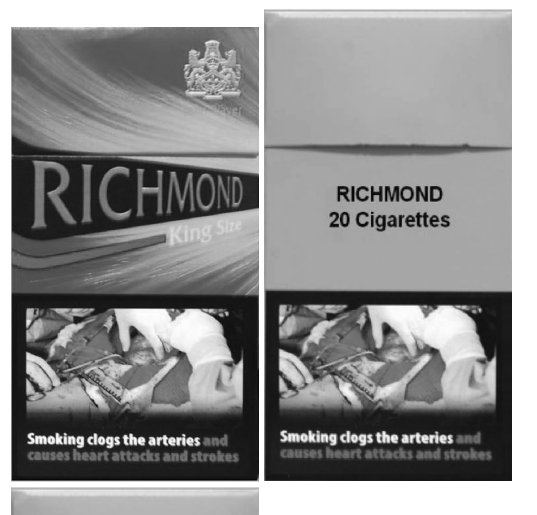

On page 3 of the linked pdf (page '1507' as marked on the pages) there is an image that is described as

- Figure 1 Examples of branded and plain pack stimuli. Example visual stimuli designed specifically for the purposes of this study are shown. Branded pack images (top) were taken from popular ciga rette brands in the United Kingdom. Plain white pack images (bottom) were taken from an example plain pack created for Action on Smoking and Health (England)

The image is reproduced here, with the bottom (plain) packet cropped off (but not entirely,) and copied to the right of the branded packet:

Note that (as apparently presented in the study) the packets are the same width, they are not the same height.

The participants

The number of participants (43, selected by adverts in and round the university campus,) while probably ideal for a feasibility study as to whether more research is needed, is pitifully small for a piece of research on which so many arguments about plain packaging appear to rest.

Additionally, for those relying on this study arguing for banning branded packaging 'for the sake of the children,' the average ages for the three groups were 23, 24 and 24 (for non-,weekly, daily respectively.) The youngest interquartile participant was 21, the oldest 28.

The male/female breakdown shows another skew:

Not that these actual numbers are actually presented in the study - they give percentages (71% of 14 daily smokers were male for example (which is 9.94.))

| Group | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| Non smokers | 10 | 5 |

| Weekly smokers | 9 | 5 |

| Daily smokers | 10 | 4 |

| Total | 29 | 14 |

Royal Holloway, University of London project

While nothing as grand as a 'study' with a published paper such as the University of Bristol study appears to pretend to be, Tim Holmes has been supervising a study by his 3rd year psychology students[2]. In his own words:

- We invited 59 non-smokers, regular smokers, social smokers (the ones who maybe smoke just on a Friday evening after a couple of drinks) and ex-smokers (who have given up for at least 6 months) to look at examples of 4 different package designs including regular branding, 2 types of picture warning labels and plain packaging. We tracked the participants’ eye-movements using a Tobii X120 eye-tracker, and showed each design with 4 different warning messages for 10 seconds each. We also asked participants to evaluate the risks associated with smoking before and after viewing the 16 packages. Unsurprisingly non-smokers tended to perceive a greater risk from smoking than the other 3 groups and disappointingly there was no change in risk perception as a result of viewing the stimuli.

- To be honest, our initial hypotheses all related to the picture messages and in the best research tradition returned non-significant results! However, we were surprised to observe two interesting results: the non-smokers looked at the warning messages much less than the other participants, and there was no difference between plain and branded package designs in the amount of time spent looking at the warning message. Now, it’s great that the right people are looking more at the warning message, but if this doesn’t result in an increased risk perception then surely the messages aren’t doing their job! Moreover, if removing the brand identity doesn’t change the way people look at the packets then maybe plain packaging, which will be costly to implement, isn’t the best of ideas.