Difference between revisions of "Standardised packaging"

Paul Herring (talk | contribs) (Created page with " Plain packaging is intended, according the the anti-smoking proponents, to reduce the number of people (some claims state 'children,' instead of people) taking up smoking becaus...") |

Paul Herring (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

Others have pointed out that plain packaging lowers the existing barriers to counterfeiting by allowing the counterfeiters to not bother too hard with one aspect of making fake cigarrettes. | Others have pointed out that plain packaging lowers the existing barriers to counterfeiting by allowing the counterfeiters to not bother too hard with one aspect of making fake cigarrettes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==J Padilla & N Watson (2008)== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''[[Media:LECG_Literature_Review_on_generic_packaging.pdf|A Critical Review Of The Literature On Generic Packaging For Cigarettes]]'', commissioned for Phillip Morris International (PMI), by The Law and Economics Consulting Group(LECG) to review: | ||

| + | |||

| + | : from a technical perspective, ten studies based on original empirical research on the issue of generic packaging of cigarettes. The selection of papers was based on a thorough review of documents discussing generic packaging as a tobacco control measure carried out by Shook Hardy & Bacon, a law firm commissioned by PMI. | ||

| + | All of the surveys reviewed purported, at least in part, to view the impact of plain packaging would have on teenager's inclination to take up smoking. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In considering whether the conclusions of the studies, in general, were accurate, it was stated that | ||

| + | |||

| + | : From our review of the studies, we conclude that they do not provide a reliable answer on the existence of a causal link between branded cigarette packaging and youth initiation to smoking. The reason is that they have limitations both in terms of the data analysis and data collection methods.5 These limitations are so fundamental that conclusions derived on the relationship between cigarette packaging and youth smoking are likely to be misleading.[Page 9] | ||

| + | ==M Goldberg, et al. (1995)== | ||

| + | ''[[Media:Canada_Expert_Panel_Report_-_When_Packages_Can't_Speak_Mar_95_-_excerpt.pdf|When Packages Can't Speak: Possible Impacts of Plain and Generic Packaging of Tobacco Products]]'' was a 1995 report based on a series of surveys, for Health Canada, of teenagers, over 5 different studies, to examine the potential effect plain packaging might have on | ||

| + | |||

| + | *the uptake of smoking to begin with, | ||

| + | |||

| + | *the impact on the recognition of, and the ability to remember, the warnings on packaging, | ||

| + | *the probability of stopping smoking | ||

| + | For the Direct Questioning surveys, Padilla and Watson(2008) summarised that | ||

| + | *Teenagers have mixed views on what they believe to be the impact of generic [plain] packaging. | ||

| + | *Results suggest that the effects of generic [plain] packaging on smoking would be marginal. | ||

| + | In the Visual Image survey that | ||

| + | *Generic packaging increased the recall rate of only one of three health warnings. The authors suggest that the exposure time was too short and that these results cannot be extrapolated to a more natural long term-setting. | ||

| + | And in the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conjoint_analysis_%28marketing%29 Conjoint] survey that | ||

| + | *Packaging is generally as important as brand influence and peer influences (except for teenage non-smokers). | ||

| + | *Results suggest that plain and generic packaging will, to some “unknown degree, encourage non-smokers not to start smoking and smokers to stop smoking” | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===National Survey=== | ||

| + | The purpose of the National Survey was to assess the knowledge, attitudes and beliefs held by teenagers (14-17 years) regarding smoking, brands, brand images, generic packaging and perceived impact of such packaging on teenagers. From an initial pool of 6,213 teenagers, 1,200 were eventually questioned from 14 Canadian cities. Those not eventually questioned dropped out because they didn't fit the age criteria, they were overt anti-smokers, or they simply refused to answer the questionairre. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''Padilla & Watson(2008)'' concluded that | ||

| + | |||

| + | : The objective of the survey was simply to provide descriptive statistics on smoking beliefs, patterns and behaviours of teens in Canada. No attempt was made to establish a causal relationship between cigarette packaging and youth smoking.[Page 40] | ||

| + | ===Word Image Survey=== | ||

| + | The purpose of this survey was to determine what, if any, differences were perceived between branded packets, plain packets or packets with a "lungs" symbol. The cohort for this study seems to have been the same cohort as the National Survey, since 1,200 took part, and they answered the same screening questions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''Padilla & Watson(2008)'' concluded that | ||

| + | |||

| + | : The results of this survey cannot be used to inform a policy decision regarding implementation of generic packaging. The likely effects of generic packaging can only be inferred from a comparison of the situation before and after the measure.[Page 42] | ||

| + | ===Visual Image Survey=== | ||

| + | Pictures of 6 (types of) people were shown with different package types (3 brands, and pack types of branded, plain or plain+"lungs",) in the lower right hand corner. Participants were then asked to agree/disagree on a 5 point scale with the statement “Consider this (picture). Is (brand name) in this package right or wrong for this (woman/man)”. The brands selected were from a previous survey for which teenagers had the greatest convergant images. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''Padilla & Watson(2008)'' again: | ||

| + | |||

| + | : By selecting only those brands that were more strongly associated with a certain person-type in the national survey, the results of this analysis may have overestimated the actual link between brands and perceived images.[Page 43] | ||

| + | ===Recall and Recognition Survey=== | ||

| + | This survey was of 400 Vancouver teenage smokers, to assess what differences plain/branded packs had on how much attention was paid to both the brand, and any warning messages present on the packs. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 3 images of a table with a packet of cigarrettes, different brand each time, (with the pack either always branded or always plain), a magazine, can of pop and a bottle of headache pills. Images were shown for 4 seconds, and the respondants asked to list what they could see, the brand of cigarettes, and the warning on the packet. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The respondants were then shown all three packs with the warnings hidden, and asked to name which warning went on which pack. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''Padilla & Watson(2008)'': | ||

| + | |||

| + | : The results of the study do not indicate that health warnings are better recalled when displayed on generic packages. | ||

| + | ===[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conjoint_analysis_%28marketing%29 Conjoint] survey=== | ||

| + | Respondants, which was the same cohort that participated in the Recall and Recognition survey above, were asked to choose between alternatives that differed in | ||

| + | *package type, | ||

| + | |||

| + | *brand, | ||

| + | |||

| + | *price, and | ||

| + | |||

| + | *peer influence (friends smoke/do not smoke). | ||

| + | ''Goldberg et al (1995)'' themselves concluded the extent of the influence of generic packaging on smoking decisions: | ||

| + | |||

| + | : cannot be validly determined by research that is dependent on asking questions about what they think or what they might do if all cigarettes sold in the same generic packages.[Page 129] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==2008 UK Department of Health Consultation== | ||

| + | In 2008 the UK DoH commissioned a consultation with the results published in a report titled Consultation on The Future of Tobacco Control[http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_085651.pdf]. In it, it reported (with emphasis added): | ||

| + | |||

| + | : Research shows that this <u>'''may'''</u> reduce the attractiveness of cigarettes and further ‘denormalise’ the use of tobacco products. Studies show that plain packaging reduces the brand appeal of tobacco products, especially among youth, with nearly half of all teenagers <u>'''believing'''</u> that plain packaging would result in fewer teenagers starting smoking.[Page 7] | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, later on it goes on to say | ||

| + | |||

| + | 3.65 The Department of Health is not aware of any precedent of legislation in any jurisdiction requiring plain packaging of tobacco products.[Page 40] | ||

| + | |||

| + | So there is no research in to what effects, if any, plain packaging elsewhere may have. | ||

==The 'University of Bristol' Study== | ==The 'University of Bristol' Study== | ||

One citation for this claim is the study entitled [http://marcus-munafo.psy.bris.ac.uk/Publications/2011%20Addiction%20b.pdf Plain packaging increases visual attention to health warnings on cigarette packs in non-smokers and weekly smokers but not daily smokers] by Marcus R. Munafò, Nicole Roberts, Linda Bauld & Ute Leonards. The title of the study pretty much sums up the findings of the study which basically involved studying the (dominant) eye movements of 15 non-smokers (never smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their life), 14 'weekly' smokers (at least one per week, but not daily) and 14 daily smokers (at least one per day.) | One citation for this claim is the study entitled [http://marcus-munafo.psy.bris.ac.uk/Publications/2011%20Addiction%20b.pdf Plain packaging increases visual attention to health warnings on cigarette packs in non-smokers and weekly smokers but not daily smokers] by Marcus R. Munafò, Nicole Roberts, Linda Bauld & Ute Leonards. The title of the study pretty much sums up the findings of the study which basically involved studying the (dominant) eye movements of 15 non-smokers (never smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their life), 14 'weekly' smokers (at least one per week, but not daily) and 14 daily smokers (at least one per day.) | ||

Revision as of 22:53, 5 March 2012

Plain packaging is intended, according the the anti-smoking proponents, to reduce the number of people (some claims state 'children,' instead of people) taking up smoking because it will "make them less attractive."

Others have pointed out that plain packaging lowers the existing barriers to counterfeiting by allowing the counterfeiters to not bother too hard with one aspect of making fake cigarrettes.

J Padilla & N Watson (2008)

A Critical Review Of The Literature On Generic Packaging For Cigarettes, commissioned for Phillip Morris International (PMI), by The Law and Economics Consulting Group(LECG) to review:

- from a technical perspective, ten studies based on original empirical research on the issue of generic packaging of cigarettes. The selection of papers was based on a thorough review of documents discussing generic packaging as a tobacco control measure carried out by Shook Hardy & Bacon, a law firm commissioned by PMI.

All of the surveys reviewed purported, at least in part, to view the impact of plain packaging would have on teenager's inclination to take up smoking.

In considering whether the conclusions of the studies, in general, were accurate, it was stated that

- From our review of the studies, we conclude that they do not provide a reliable answer on the existence of a causal link between branded cigarette packaging and youth initiation to smoking. The reason is that they have limitations both in terms of the data analysis and data collection methods.5 These limitations are so fundamental that conclusions derived on the relationship between cigarette packaging and youth smoking are likely to be misleading.[Page 9]

M Goldberg, et al. (1995)

When Packages Can't Speak: Possible Impacts of Plain and Generic Packaging of Tobacco Products was a 1995 report based on a series of surveys, for Health Canada, of teenagers, over 5 different studies, to examine the potential effect plain packaging might have on

- the uptake of smoking to begin with,

- the impact on the recognition of, and the ability to remember, the warnings on packaging,

- the probability of stopping smoking

For the Direct Questioning surveys, Padilla and Watson(2008) summarised that

- Teenagers have mixed views on what they believe to be the impact of generic [plain] packaging.

- Results suggest that the effects of generic [plain] packaging on smoking would be marginal.

In the Visual Image survey that

- Generic packaging increased the recall rate of only one of three health warnings. The authors suggest that the exposure time was too short and that these results cannot be extrapolated to a more natural long term-setting.

And in the Conjoint survey that

- Packaging is generally as important as brand influence and peer influences (except for teenage non-smokers).

- Results suggest that plain and generic packaging will, to some “unknown degree, encourage non-smokers not to start smoking and smokers to stop smoking”

National Survey

The purpose of the National Survey was to assess the knowledge, attitudes and beliefs held by teenagers (14-17 years) regarding smoking, brands, brand images, generic packaging and perceived impact of such packaging on teenagers. From an initial pool of 6,213 teenagers, 1,200 were eventually questioned from 14 Canadian cities. Those not eventually questioned dropped out because they didn't fit the age criteria, they were overt anti-smokers, or they simply refused to answer the questionairre.

Padilla & Watson(2008) concluded that

- The objective of the survey was simply to provide descriptive statistics on smoking beliefs, patterns and behaviours of teens in Canada. No attempt was made to establish a causal relationship between cigarette packaging and youth smoking.[Page 40]

Word Image Survey

The purpose of this survey was to determine what, if any, differences were perceived between branded packets, plain packets or packets with a "lungs" symbol. The cohort for this study seems to have been the same cohort as the National Survey, since 1,200 took part, and they answered the same screening questions.

Padilla & Watson(2008) concluded that

- The results of this survey cannot be used to inform a policy decision regarding implementation of generic packaging. The likely effects of generic packaging can only be inferred from a comparison of the situation before and after the measure.[Page 42]

Visual Image Survey

Pictures of 6 (types of) people were shown with different package types (3 brands, and pack types of branded, plain or plain+"lungs",) in the lower right hand corner. Participants were then asked to agree/disagree on a 5 point scale with the statement “Consider this (picture). Is (brand name) in this package right or wrong for this (woman/man)”. The brands selected were from a previous survey for which teenagers had the greatest convergant images.

Padilla & Watson(2008) again:

- By selecting only those brands that were more strongly associated with a certain person-type in the national survey, the results of this analysis may have overestimated the actual link between brands and perceived images.[Page 43]

Recall and Recognition Survey

This survey was of 400 Vancouver teenage smokers, to assess what differences plain/branded packs had on how much attention was paid to both the brand, and any warning messages present on the packs.

3 images of a table with a packet of cigarrettes, different brand each time, (with the pack either always branded or always plain), a magazine, can of pop and a bottle of headache pills. Images were shown for 4 seconds, and the respondants asked to list what they could see, the brand of cigarettes, and the warning on the packet.

The respondants were then shown all three packs with the warnings hidden, and asked to name which warning went on which pack.

Padilla & Watson(2008):

- The results of the study do not indicate that health warnings are better recalled when displayed on generic packages.

Conjoint survey

Respondants, which was the same cohort that participated in the Recall and Recognition survey above, were asked to choose between alternatives that differed in

- package type,

- brand,

- price, and

- peer influence (friends smoke/do not smoke).

Goldberg et al (1995) themselves concluded the extent of the influence of generic packaging on smoking decisions:

- cannot be validly determined by research that is dependent on asking questions about what they think or what they might do if all cigarettes sold in the same generic packages.[Page 129]

2008 UK Department of Health Consultation

In 2008 the UK DoH commissioned a consultation with the results published in a report titled Consultation on The Future of Tobacco Control[1]. In it, it reported (with emphasis added):

- Research shows that this may reduce the attractiveness of cigarettes and further ‘denormalise’ the use of tobacco products. Studies show that plain packaging reduces the brand appeal of tobacco products, especially among youth, with nearly half of all teenagers believing that plain packaging would result in fewer teenagers starting smoking.[Page 7]

However, later on it goes on to say

3.65 The Department of Health is not aware of any precedent of legislation in any jurisdiction requiring plain packaging of tobacco products.[Page 40]

So there is no research in to what effects, if any, plain packaging elsewhere may have.

The 'University of Bristol' Study

One citation for this claim is the study entitled Plain packaging increases visual attention to health warnings on cigarette packs in non-smokers and weekly smokers but not daily smokers by Marcus R. Munafò, Nicole Roberts, Linda Bauld & Ute Leonards. The title of the study pretty much sums up the findings of the study which basically involved studying the (dominant) eye movements of 15 non-smokers (never smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their life), 14 'weekly' smokers (at least one per week, but not daily) and 14 daily smokers (at least one per day.)

Specifically, they measured how long people looked at the warning messages on both plain and branded packs, and the difference in amount of time between the types of packs and the types of smokers.

Participants were instructed that they'd be shown some images in the first phase of the experiment, and would have to indicate whether or not any images presented in the second phase were present in the first.

The first phase consisted of (randomly) 10 images of plain packs and 10 images of branded packs with 10 warnings (one per type of pack) present and each image was shown for 10 seconds.

The second phase, was 10 images from phase 1, and 10 new images (with each set of 10 having 5 plain and 5 branded packs, and 5 warnings,) and the participants given 5 seconds per image to decide if it was present in phase 1 or not.

Eye movements were tracked in only the first phase.

As summarised by the study's titile, they found that the non- and weekly- smokers tended to look at the warning more if the pack was plain than if it was branded.

Problems with the Bristol Study

The images used

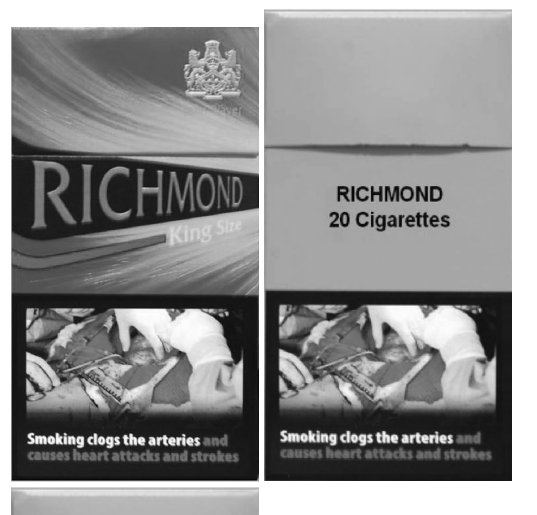

On page 3 of the linked pdf (page '1507' as marked on the pages) there is an image that is described as

- Figure 1 Examples of branded and plain pack stimuli. Example visual stimuli designed specifically for the purposes of this study are shown. Branded pack images (top) were taken from popular ciga rette brands in the United Kingdom. Plain white pack images (bottom) were taken from an example plain pack created for Action on Smoking and Health (England)

The image is reproduced here, with the bottom (plain) packet cropped off (but not entirely,) and copied to the right of the branded packet:

Note that (as apparently presented in the study) the packets are the same width, they are not the same height.

The participants

The number of participants (43, selected by adverts in and round the university campus,) while probably ideal for a feasibility study as to whether more research is needed, is pitifully small for a piece of research on which so many arguments about plain packaging appear to rest.

Additionally, for those relying on this study arguing for banning branded packaging 'for the sake of the children,' the average ages for the three groups were 23, 24 and 24 (for non-,weekly, daily respectively.) The youngest interquartile participant was 21, the oldest 28.

The male/female breakdown shows another skew:

| Group | Male | Female | Non smokers | 10 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weekly smokers | 9 | 5 | |||

| Daily smokers | 10 | 4 | |||

| Total | 29 | 14 |

Not that these actual numbers are actually presented in the study - they give percentages (71% of 14 daily smokers were male for example (which is 9.94.))

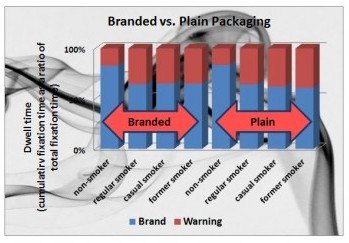

Royal Holloway, University of London project

While nothing as grand as a 'study' with a published paper such as the University of Bristol study appears to pretend to be, Tim Holmes has been supervising a study by his 3rd year psychology students[2]. In his own words:

- We invited 59 non-smokers, regular smokers, social smokers (the ones who maybe smoke just on a Friday evening after a couple of drinks) and ex-smokers (who have given up for at least 6 months) to look at examples of 4 different package designs including regular branding, 2 types of picture warning labels and plain packaging. We tracked the participants’ eye-movements using a Tobii X120 eye-tracker, and showed each design with 4 different warning messages for 10 seconds each. We also asked participants to evaluate the risks associated with smoking before and after viewing the 16 packages. Unsurprisingly non-smokers tended to perceive a greater risk from smoking than the other 3 groups and disappointingly there was no change in risk perception as a result of viewing the stimuli.

- To be honest, our initial hypotheses all related to the picture messages and in the best research tradition returned non-significant results! However, we were surprised to observe two interesting results: the non-smokers looked at the warning messages much less than the other participants, and there was no difference between plain and branded package designs in the amount of time spent looking at the warning message. Now, it’s great that the right people are looking more at the warning message, but if this doesn’t result in an increased risk perception then surely the messages aren’t doing their job! Moreover, if removing the brand identity doesn’t change the way people look at the packets then maybe plain packaging, which will be costly to implement, isn’t the best of ideas.