Difference between revisions of "Internet anonymity"

Paul Herring (talk | contribs) |

Paul Herring (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

{{quote|Commentators often attempt to refute the nothing-to-hide argument by pointing to things people want to hide. But the problem with the nothing-to-hide argument is the underlying assumption that privacy is about hiding bad things. By accepting this assumption, we concede far too much ground and invite an unproductive discussion about information that people would very likely want to hide. As the computer-security specialist Schneier aptly notes, the nothing-to-hide argument stems from a faulty "premise that privacy is about hiding a wrong." Surveillance, for example, can inhibit such lawful activities as free speech, free association, and other First Amendment rights essential for democracy. <ref>[http://chronicle.com/article/Why-Privacy-Matters-Even-if/127461/ Why Privacy Matters Even if You Have 'Nothing to Hide'] - The Chronicle of Higher Education - Washington DC</ref>}} | {{quote|Commentators often attempt to refute the nothing-to-hide argument by pointing to things people want to hide. But the problem with the nothing-to-hide argument is the underlying assumption that privacy is about hiding bad things. By accepting this assumption, we concede far too much ground and invite an unproductive discussion about information that people would very likely want to hide. As the computer-security specialist Schneier aptly notes, the nothing-to-hide argument stems from a faulty "premise that privacy is about hiding a wrong." Surveillance, for example, can inhibit such lawful activities as free speech, free association, and other First Amendment rights essential for democracy. <ref>[http://chronicle.com/article/Why-Privacy-Matters-Even-if/127461/ Why Privacy Matters Even if You Have 'Nothing to Hide'] - The Chronicle of Higher Education - Washington DC</ref>}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Of course, forcing everyone to use their real names won't solve the perceived problems of 'anonymity' as these two reports about Facebook show: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{quote|Judge Nigel Gilmour, sitting at Liverpool Crown Court[UK], said the site [Facebook] fuelled a violent attack by Daniel Cannon, 17, in which he used "his teeth as a weapon" to bite off a chunk of friend's ear. | ||

| + | |||

| + | "It is remarkable when people are communicating on Facebook that they say things they would not say face to face," said the judge. | ||

| + | |||

| + | "We are increasingly getting in court instances beginning on Facebook, it is becoming more and more." | ||

| + | |||

| + | He hit out over messages posted on Facebook by Cannon's brother, which provoked the attack.<ref>[http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/facebook/9571086/Facebook-is-fuelling-violence-claims-judge.html Facebook is fuelling violence, claims judge] - The Telegraph]</ref>}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{quote|Jennifer Bristol recently lost [as a friend] one of her oldest friends—thanks to a Facebook fight about pit bulls. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [...] | ||

| + | |||

| + | The trouble started when she posted a newspaper article asserting that pit bulls were the most dangerous type of dog in New York City last year. "Please share thoughts… 833 incidents with pitties," wrote Ms. Bristol, a 40-year-old publicist and animal-welfare advocate in Manhattan. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Her friends, many of whom also work in the animal-welfare world, quickly weighed in. One noted that "pit bull" isn't a single official breed; another said "irresponsible ownership" is often involved when dogs turn violent. Black Labs may actually bite more, someone else offered. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Then a childhood pal of Ms. Bristol piped up with this: "Take it from an ER doctor… In 15 years of doing this I have yet to see a golden retriever bite that had to go to the operating room or killed its target." | ||

| + | |||

| + | That unleashed a torrent. One person demanded to see the doctor's "scientific research." Another accused him of not bothering to confirm whether his patients were actually bitten by pit bulls. Someone else suggested he should "venture out of the ER" to see what was really going on. | ||

| + | |||

| + | "It was ridiculous," says Ms. Bristol, who stayed out of the fight. Her old buddy, the ER doctor, unfriended her the next morning. That was eight months ago. She hasn't heard from him since.<ref>[http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10000872396390444592404578030351784405148.html Why We Are So Rude Online] - Wall Street Journal</ref>}} | ||

Latest revision as of 21:08, 3 October 2012

Nearly every week, if not every day, certainly in the United Kingdom, there are calls from one group of people or another for a ban on what is considered 'internet anonymity.'

The fact that, for the vast majority of people who use the internet, anonymity on the internet is a very high bar to achieve, what most of these calls are for is for people to be instantly recognisable whenever they produce content on the internet, be it a MediaWiki site such as this or Wikipedia, to the comments section beneath any news story on your local paper's website; it's just very difficult, for the normal person, to verify that a particular comment was made by a particular person.

Those fighting for the removal of 'internet anonymity' want everyone on the internet to be able to tell who everyone else is easily.

Those defending 'internet anonymity' want to be able to post 'anonymously' without fear of retribution from, for example, their employers - regardless of whether what they're saying has anything to do with their employers. Or their neighbours (again - regardless of whether it has anything to do with them or not.)

Just because there are people who feel the need to advertise themselves publicly on Facebook, for example, including their every (bowel) movement, that does not mean that everyone is willing to give up their right not to be (easily) identified by their real-life peers on the internet. They want their privacy, and moves to remove 'internet anonymity' attempt to remove that privacy.

Commentators often attempt to refute the nothing-to-hide argument by pointing to things people want to hide. But the problem with the nothing-to-hide argument is the underlying assumption that privacy is about hiding bad things. By accepting this assumption, we concede far too much ground and invite an unproductive discussion about information that people would very likely want to hide. As the computer-security specialist Schneier aptly notes, the nothing-to-hide argument stems from a faulty "premise that privacy is about hiding a wrong." Surveillance, for example, can inhibit such lawful activities as free speech, free association, and other First Amendment rights essential for democracy. [1]

Of course, forcing everyone to use their real names won't solve the perceived problems of 'anonymity' as these two reports about Facebook show:

Judge Nigel Gilmour, sitting at Liverpool Crown Court[UK], said the site [Facebook] fuelled a violent attack by Daniel Cannon, 17, in which he used "his teeth as a weapon" to bite off a chunk of friend's ear.

"It is remarkable when people are communicating on Facebook that they say things they would not say face to face," said the judge.

"We are increasingly getting in court instances beginning on Facebook, it is becoming more and more."

He hit out over messages posted on Facebook by Cannon's brother, which provoked the attack.[2]

Jennifer Bristol recently lost [as a friend] one of her oldest friends—thanks to a Facebook fight about pit bulls.

[...]

The trouble started when she posted a newspaper article asserting that pit bulls were the most dangerous type of dog in New York City last year. "Please share thoughts… 833 incidents with pitties," wrote Ms. Bristol, a 40-year-old publicist and animal-welfare advocate in Manhattan.

Her friends, many of whom also work in the animal-welfare world, quickly weighed in. One noted that "pit bull" isn't a single official breed; another said "irresponsible ownership" is often involved when dogs turn violent. Black Labs may actually bite more, someone else offered.

Then a childhood pal of Ms. Bristol piped up with this: "Take it from an ER doctor… In 15 years of doing this I have yet to see a golden retriever bite that had to go to the operating room or killed its target."

That unleashed a torrent. One person demanded to see the doctor's "scientific research." Another accused him of not bothering to confirm whether his patients were actually bitten by pit bulls. Someone else suggested he should "venture out of the ER" to see what was really going on.

"It was ridiculous," says Ms. Bristol, who stayed out of the fight. Her old buddy, the ER doctor, unfriended her the next morning. That was eight months ago. She hasn't heard from him since.[3]

Anonymity?

IP Addresses

In reality, it is very difficult to be totally anonymous on the internet.

Every time you access a web page, you leave behind a record of which ISP you are using via your IP address in that sites logs.

Whether the general public can obtain that data is up to the site, but in general it's not something that's immediately accessible to someone who isn't actually involved with the site.

For example, on most MediaWiki sites, if you aren't logged in, any changes you make are recorded against your IP address. On the Revision History page of Wikipedia's Anonymity article taken on the evening of 26 Sep 2012 we have:

(cur | prev) 00:27, 9 June 2012 Trident13 (talk | contribs) . . (18,241 bytes) (+25) . . (→See also: * Anonymous blogging) (undo)

(cur | prev) 20:32, 18 May 2012 Adjwilley (talk | contribs) . . (18,216 bytes) (-2) . . (Good faith revert of edit(s) by 198.189.235.79 using STiki all caps) (undo)

(cur | prev) 20:28, 18 May 2012 198.189.235.79 (talk) . . (18,218 bytes) (+2) . . (→Mathematics of anonymity) (undo)

(cur | prev) 20:28, 18 May 2012 198.189.235.79 (talk) . . (18,216 bytes) (0) . . (undo)

(cur | prev) 05:40, 25 March 2012 Wiki141592 (talk | contribs) . . (18,216 bytes) (-372) . . (removed 'trend' statement; 2009 quote with no citation; and minor edits) (undo)[4]Shown with a darker background, we have two entries by 'username' 192.189.235.79 - this is an 'anonymous' user who edited the page.

Asking one of the numerous services on the internet dedicated to such things, if you put http://whois.arin.net/rest/nets;q=192.189.235.79?showDetails=true&showARIN=false&ext=netref2 into your browser you'll find that the company that owns that IP address (along with 255 others in this particular part of the address space) is Center for Naval Analyses.

With that information, if you want to know who made those edits, then you simply contact the CNA, and ask them "who, at 20:28 on the 18th May 2012, had 198.189.235.79 as their IP address."

Problems with IP addresses

Naturally the CNA could tell you to bugger off; and if the ISP concerned was a large one - like Verizon in the states - getting this information out requires slightly more than just a request; a warrant at the absolute minimum would typically be needed.

Additionally the authority responsible for the IP address concerned might not keep records (likely for CNA,) or they may not keep them long enough. But the theory is there - if you have an IP address and a time, it gives you sufficient information to at least get you close, if not at, the person concerned.

Unless, of course, the IP address is the single public address for a company, or a household. If you have wireless in your house, and you have more than one computer accessing the internet, then all your devices will have (to the websites they visit) exactly the same IP address. But then asking Verizon who had an IP address at a particular date still gives you the household that visited the site, and deciding who's responsible for behaviour in that household is a favourite topic of companies like the RIAA.

With companies with all their employees behind the same, the process of discovery is usually a bit trickier, but ultimately (depending on that company's own logs) it can be done; supplying them with (e.g.) an additional URL they can use to search their logs will usually allow them to find who, internally, was (ab)using a site. (Most companies record what their employees are doing on the internet. Generally no-one actually looks at them without reason, but they are recorded.)

Nicknames/Nom-de-plumes

Most private commentators on the internet tend to pick a 'handle' and try to stick to it on every forum/blog/website that uses usernames. Some of these names enter the public conciousness as 'real names,' such as when the Tobacco Tactics website wrote a page on Dick Puddlecote and stated, without apparent irony, that

..Puddlecote says he runs his own transport business, yet there is no "Puddlecote" listed as a Director at Companies House. [5]

Seriously, though, most times when you see a distinctive name you recognise somewhere on the internet, it will one of three possibilities:

- the person you think it is, using the same name elsewhere

- a completely different person who thought of the same name or

- someone trying to impersonate one of the above two

.. and generally, you can tell which of them it is. Most people are happy with this situation, and feel that the voluntary nature of it lacks the bully-stateism seen evidenced elsewhere on this website.

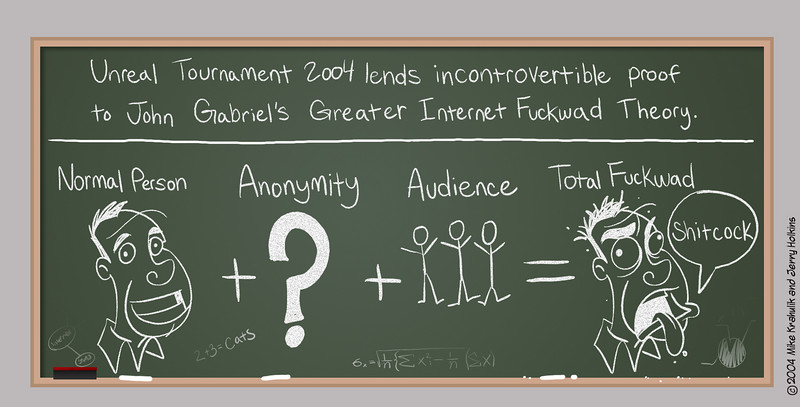

Where this falls down, of course, is the sites that don't force such usernames tend to bring out the people who exhibit what Wikipedia calls Online Disinhibition Effect, or as most on the internet know it 'John Gabriel's "Greater Internet Fuckwad Theory"' illustrated by this Penny Arcade comic back from 2004:

And as with minimum pricing, the solutions generally proposed inconvenience, annoy, and evoke a whole range of other negative emotions in the vast majority of the population (who care about such things) who aren't the problem, to try and fix the problem with the small minority, without actual evidence that the proposal will actually fix the problem with the small minority.

In real life

Jonathan Myerson - Guardian - 27 Aug 2012

Myerson quotes the South Korean law that was rescinded (mentioned below) seemingly as if it was a bad thing:

When South Korea recently introduced a law demanding all online users identify themselves before posting to message boards, a Carnegie Mellon study of the effects showed that online participation did not drop in the long term but "uninhibited behaviours" certainly did: "swear words and anti-normative expressions" were significantly reduced.

In spite of this, last week the law was overturned by a constitutional court on the grounds that it was violating freedom of speech.[6]

Perhaps, deliberately, ignoring the fact that it was viewed as a method by the Korean government to chill free speech, especially political speech.

Myerson goes on:

Introducing the law, a national assembly member declared that "internet space in our country has become the wall of a public toilet". [6]

.. failing to spot the fact that there wasn't just one law, there were a series of laws going back to 2003 through to at least 2010, and in his apparent exuberant haste to use a quote with the word 'toilet' in it, Myerson appears to have failed to give hints to which national assembly member it was, why this quote was made, and when it was made.

In fact it was the suicide of Choi Jin-sil, whose suicide was 'blamed' on the internet, and the quote comes from 4 years previously (perhaps there weren't any more recent toilet quotes to be used?):

The police, the media and members of Parliament immediately pointed fingers at the Internet. Malicious online rumors led to Ms. Choi’s suicide, the police said, after studying memos found at her home and interviewing friends and relatives.

Those online accusations claimed that Ms. Choi, who once won a government medal for her savings habits, was a loan shark. They asserted that a fellow actor, Ahn Jae-hwan, was driven to suicide because Ms. Choi had relentlessly pressed him to repay a $2 million debt.

Public outrage over Ms. Choi’s suicide gave ammunition to the government of President Lee Myung-bak, which has long sought to regulate cyberspace, a major avenue for antigovernment protests in South Korea.

[...]

Hong Joon-pyo, floor leader of the governing Grand National Party, commented, “Internet space in our country has become the wall of a public toilet.” [7]

Myerson then goes on to ignore the privacy issue with 'real names on the internet':

But imagine (as I have done for a new play) if all user names magically reverted to the individuals' real names. Go on, think about it – what would actually be different? What, most importantly, would be lost? What have you ever posted – on a discussion board, or Twitter or elsewhere – to which you are not willing to put your name?[6]

Well, for a start, there's all those gay people who are 'in the closet' who aren't too keen on being outed at a time not of their choosing.

Not too keen on gay-rights? How about those vocal on the internet about matters political, who if their views were known to their friends/relatives, would be ostracised?

Oops - back to the chilling of political speech there. Don't want that.

What about whistle-blowers? Ah - Myerson has a solution!

And what of whistleblowers? To this, an easy answer: the Royal Mail. Didn't whistleblowing exist before the advent of the internet? To speak freely, to be outspoken – even highly and outspokenly critical – is of course one of the most treasured rights of a free society.[6]

Meyerson, however misses the point that people want to be 'in the closet' or 'have political views' or to use his own words 'to speak freely, to be outspoken,' and 'critical' on the internet, and his 'solution...' isn't one.

And from the summary of another commentator on this article:

My online persona is but a thin veneer, so is relatively easily uncovered. I use it, however, because I choose to keep this part of my life separate from other parts of my life, just as I keep my professional world and personal one in separate boxes. This is my choice – it is not the choice of totalitarian control freaks who write risible articles on CiF who feel threatened because we do for free what they are paid for, to make it for me – and, frankly, many do it a damned sight better. And, as I pay for this place, the name I choose to use is up to me, not some shit-bag writing in the Groan. Go fuck yourself.[8]

South Korea online verification law rescinded - Aug 2012

From 2003, South Korea had introduced a mechanism whereby some people using the internet had to verify themselves, culminating in 2010 where anyone posting to the internet had to verify their identity:

Real-name registration requirements have been a part of the South Korean Internet landscape since 2003, when the MIC sought the cooperation of four major Web portals (Yahoo Korea, Daum Communications, NHN, and NeoWiz) in developing real-name systems for their users. While implicating deeper privacy concerns, the purported goal of real-name measures is to reduce abusive behavior on the Internet. A number of prominent cases (such as the suicides of a number of actresses) have made this a major issue for the Korean public.

In 2004 election laws began requiring individuals who post comments on Web sites and message boards in support of, or in opposition to, a candidate to disclose their real names. In 2005 the government implemented a rule that required e-mail or chat-service account holders to provide detailed information, including name, address, profession, and identification number. This policy was tightened further by the MIC in July 2007 when users were required to register their real names and resident identification numbers with Web sites before posting comments or uploading video or audio clips on bulletin boards. In December 2008, the KCC extended its reach to require all forum and chat room users to make verifiable real-name registrations. Furthermore, an April 2009 amendment to the Information Act took effect, requiring Korea-domain Web sites with at least 100,000 visitors daily to confirm personal identities through real names and resident registration numbers[9]

This was eventually overturned in Aug 2012 by a court when free-speech advocates claimed the laws were being used as a chilling-effect against political dissidents and was curtailing free speech:

But free-speech advocates condemned the rule, arguing that the government was using perceived abuses as a convenient excuse to discourage political criticism. They feared that people would censor themselves rather than provide their names, which would make it easier for the government to find and possibly punish them.

[...]

On Thursday [20th Sep 2012?], an eight-judge Constitutional Court panel unanimously ruled that the restriction violated the right to free speech.

“Restriction on freedom of expression can be justified only when it is clear that it benefits public interests,” the court said in its verdict. “It’s difficult to say that the regulation is achieving public interests.” [10]

References

- ↑ Why Privacy Matters Even if You Have 'Nothing to Hide' - The Chronicle of Higher Education - Washington DC

- ↑ Facebook is fuelling violence, claims judge - The Telegraph]

- ↑ Why We Are So Rude Online - Wall Street Journal

- ↑ Revision History of Anonymity from Wikipedia - WebCitation taken 26 Sep 2012

- ↑ WebCite taken on 26th Nov 2012 of Dick Puddlecote - Tobacco Tactics

- ↑ a b c d The web has become a bizarre synthesis of toilet wall and Thomas Paine - The Guardian

- ↑ Korean Star’s Suicide Reignites Debate on Web Regulation - New York Times; 12 Oct 2008

- ↑ And Hot on the Heels… - Longrider blog

- ↑ South Korea - OpenNet Inititive

- ↑ South Korean Court Rejects Online Name Verification Law - New York Times