Standardised packaging

Plain packaging is intended, according the the anti-smoking proponents, to reduce the number of people (some claims state 'children,' instead of people) taking up smoking because it will "make them less attractive."

Others have pointed out that plain packaging lowers the existing barriers to counterfeiting by allowing the counterfeiters to not bother too hard with one aspect of making fake cigarrettes.

MPs Open Letter[1] to Secratary of State for Health (Jul 2012)

In July 2012, 50 cross-party Members of Parliament signed an open[1] letter to the Secratary of State for Health (Andrew Lansley) pointing out perceived flaws in Plain Packaging, mentioning

There is no reliable evidence that plain packaging will have any public health benefit; no country in the world has yet to introduce it. However such a measure could have extremely negative consequences elsewhere. This proposal will be a smuggler's charter. Latest estimates from HM Revenue and Customs show that up to 16% of cigarettes and 50% of hand-rolling tobacco in the UK is smuggled [...] standardised packaging [could] make smuggling simpler and exacerbate [lost revenue to HMRC].

... this policy threatens more than 5,500 jobs directly employed by the UK tobacco sector and over 65,000 valued jobs in the associated supply chain.

... we believe products must be afforded certain basic commercial freedoms. The forcible removal of branding would infringe fundamental legal rights, severely damage principles around intellectual property and set a dangerous precedent for the future of commercial free speech. Indeed, if the Department of Health were to introduce standardised packaging for tobacco products, would it also do the same for alcohol, fast food, chocolate and all other products deemed unhealthy for us?

Ford (2012)

A Cancer Research UK funded study of 48 Scottish 15-yr-olds which prompted stories of "Tobacco companies are designing cigarette packs to resemble bottles of perfume or with lids that flip open like a lighter to lure young people into smoking"[2] but in fact shows that teenagers are remarkably unaware of current packaging, and thus plain packaging will serve no useful purpose in reducing the likelihood of teenagers taking up smoking.

Borland, Savvas (2012)

An internet survey of only 160 young Australian smokers, for Tobacco Control, were shown different formats of cigarettes differing by shape, patterning of the filter end, and branding concludes, that the format of the cigarettes themselves should be standardised as 'plain' because of the participants' perceptions that branded cigarettes with cork-patterned filters are higher in quality and stronger in taste

London Economics (2012)

The results of surveying 3,000 people on the effects of the removal of various 'product signals' (such as the branding, or other differentiators between brands) on various products (i.e. not just tobacco) suggest that plain packaging would result in customers buying cheaper brands for lack of any other signals to select brands on. This could result in the average price of cigarettes dropping, and tobacco companies further reducing their prices to maintain market share. Furthermore:

- "If greater price competition were to occur (and given the importance of price signals in the marketplace), there may be a possible increase in the level of consumption, especially amongst those individuals with fewer financial resources. Other factors held constant, the removal of all packaging imagery and possible subsequent price falls may also encourage younger people to take up smoking in the first instance."

J Padilla & N Watson (2008)

Commissioned for Phillip Morris International (PMI), by The Law and Economics Consulting Group(LECG) to review previous research on the subject of generic (plain) packaging, largely with regard to teenagers. It concludes that none of those papers reviewed could provide a reliable basis on which to determine if plain packaging would reduce smoking levels.

M Goldberg, et al. (1995)

A report for Health Canada, of teenagers, over 5 different studies, to examine the potential effect plain packaging might have on

- the uptake of smoking to begin with,

- the impact on the recognition of, and the ability to remember, the warnings on packaging,

- the probability of stopping smoking

The surveys were largely about what teenagers think they'd do, and not what they'd actually do, with regard to plain packaging.

Department of Health (2008)

Entitled Consultation on the future of tobacco control, aimed at "PCT CEs, NHS Trust CEs, SHA CEs, Foundation Trust CEs, Medical Directors, Directors of PH, Directors of Nursing, Local Authority CEs, Communications Leads," this report came up with a lot of conclusions that contained the words 'may,' 'might,' 'could' and other weasel words.

It was also very selective in quoting parts of other research, while ignoring the parts that contradicted the, perceived, desired outcome for this report.

Munafò, Roberts, Bauld & Leonards (2011)

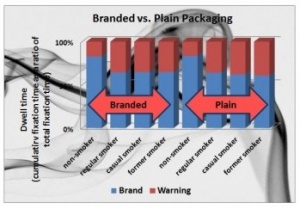

A study, by the University of Bristol, on of the eye movements of 43 (either largely or solely) university-age students when presented with images of both branded and plain packs.

Problems with the study include disparity in the size of packs used between branded and plain packs, and the small number of participants (less than 25 in each of the three cohorts) with a total male/female ratio of 2/1 and what is presumed to be a narrow age range (average age was 23/24.)

A more serious problem with this study is that it reports its results as being an effect of "salience", which if true, affects low-level, bottom-up visual processes and so should produce similar results in ALL participants, whereas they only find a significant effect for non-smokers and weekly smokers (average of about 8 per week) with NO EFFECT for regular smokers.

Royal Holloway, University of London project

While nothing as grand as a 'study' with a published paper such as the University of Bristol study appears to pretend to be, Tim Holmes has been supervising a study by his 3rd year psychology students[1]. In his own words:

- We invited 59 non-smokers, regular smokers, social smokers (the ones who maybe smoke just on a Friday evening after a couple of drinks) and ex-smokers (who have given up for at least 6 months) to look at examples of 4 different package designs including regular branding, 2 types of picture warning labels and plain packaging. We tracked the participants’ eye-movements using a Tobii X120 eye-tracker, and showed each design with 4 different warning messages for 10 seconds each. We also asked participants to evaluate the risks associated with smoking before and after viewing the 16 packages. Unsurprisingly non-smokers tended to perceive a greater risk from smoking than the other 3 groups and disappointingly there was no change in risk perception as a result of viewing the stimuli.

- To be honest, our initial hypotheses all related to the picture messages and in the best research tradition returned non-significant results! However, we were surprised to observe two interesting results: the non-smokers looked at the warning messages much less than the other participants, and there was no difference between plain and branded package designs in the amount of time spent looking at the warning message. Now, it’s great that the right people are looking more at the warning message, but if this doesn’t result in an increased risk perception then surely the messages aren’t doing their job! Moreover, if removing the brand identity doesn’t change the way people look at the packets then maybe plain packaging, which will be costly to implement, isn’t the best of ideas.