Standardised packaging

Plain packaging is intended, according the the anti-smoking proponents, to reduce the number of people (some claims state 'children,' instead of people) taking up smoking because it will "make them less attractive."

Others have pointed out that plain packaging lowers the existing barriers to counterfeiting by allowing the counterfeiters to not bother too hard with one aspect of making fake cigarettes.

Mexico has recently (Jul 2012) made a request of the Australian government for evidence of the efficacy of plain packaging[PDF], in particular, back in May 2011:

2. Provide the scientific information available in which Australia determined that plain packaging influences consumer behavior, which will contribute to reduce smoking rates and explain the justification of the technical regulations in terms of the provisions of paragraphs 2 to 4 of article 2 of the TBT Agreement. [1]

However Australia's Federal Health Minister Nicola Roxon has explicitly stated[PDF] that:

Journalist: Minister, some members of the Opposition say they are keen to reduce the incidence of smoking, but they say you have no proof that this will actually do it.

Nicola Roxon: Well, this is a world first. The sort of proof they're looking for doesn't exist when this hasn't been introduced around the world. We do have research that tests the interest in particular measures, tests whether or not you can make a packet less attractive, whether it makes a person less likely to buy a product. We can't look around the world to see these successes because it hasn't been introduced around the world. [2]

As pointed out elsewhere, querying people on what they think they might do, isn't measuring what they will actually do.

More recently Ms Roxon has stated in August 2012:

"We've been very clear - we haven't made any estimates about the level of reduction that will flow from plain packaging," she told Sky News on Sunday[3]

Review of UK Government's 2012 consultation - Jan 2013

A review[4] paid for by PMI concluded that the UK Government's 2012 consultation on 'standardised packaging' for tobacco was seriously flawed for four reasons:

- The questions were skewed towards the conclusion that plain packaging would be adopted as presented without producing a clear baseline of what would happen should it be found that plain packaging should not be adopted, or proffering policymakers with a 'half-way' house between full adoption or doing nothing. Essentially, the following loaded question was offered: "Are you in favour of standardised packaging or do you want teens and young people to start smoking?"

- Evidence proffered was questionable, and misleading inferences were drawn from said evidence. For example the presumption that there is a link between packaging and smoking. No relationship was actually demonstrated to exist, and certainly no evidence given.

- The DoH actually admitted that the consultation was prone to bias, yet made no attempt at correcting or mitigating it.

- No attempt was made to examine the unintended consequences of applying a plain packaging policy, for example removing all visual differences between packets would likely result in the determining difference being price with a consequent result. Nor was the potential for increased illicit tobacco examined.

Lancet - next: alcohol and food - 25 Aug 2012

Like many other milestone tobacco-control legislations such as pictorial warnings on tobacco packets, first adopted by Canada in 2001, and workplace smoking bans, first introduced in Ireland in 2004, Australia's lead in plain packaging will inevitably be followed by many other countries. Indeed, the UK, Norway, New Zealand, Canada, India, and South Africa are already considering taking such measures. Furthermore, the valuable lessons learnt in the fight against tobacco can be taken on board in countering the rampant marketing of alcohol and fast food.[5]

Belies the protestations against the slippery slope argument used in the tobacco template.

Australian government may implement tax rise to coincide with introduction of plain packaging - 5 Sep 2012

The price of cigarettes would rise to $20 a pack under a Gillard Government proposal that would reap an extra $1.25 billion a year in taxes.

The West Australian understands the Government is considering a 25 per cent rise in tobacco excise that would raise $5 billion over four years.

[...]

The excise increase may be timed to coincide with the introduction of mandatory plain-packaging for tobacco products on December 1.[6]

Now it may be rather cynical to suggest that such a huge tax rise may result in fewer cigarettes that raise such taxes being bought and - given the timing - the tax rise may be forgotten, and the reason given for the decrease will be plain packaging.

To place the cost into perspective, in Feb 2007 a typical packet of 25 cigarettes cost AU$11.25[7] of which $7.03 was tax (both excise and service) (62.5%)

Australian plain packaging doesn't result in a decrease in sales

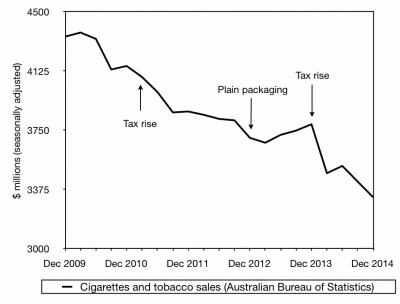

As the graph below shows, plain packaging does not seem to have led to an acceleration in the decline of tobacco sales. On the contrary, the first year in which plain packaging was in force was the first time since the 1990s that sales rose in three consecutive quarters.[8]

Attwood, Scott-Samuel, Stothart, Munafò (2012) - 3 Sep 2012

In a study that finds it takes longer to drink a poncy French lager if you put it in a straight glass than it would if it was either lager or a soft drink in a fluted glass, they discuss the current state of affairs in the UK with regard to the variety of glasses available in pubs in which drinks may be served:

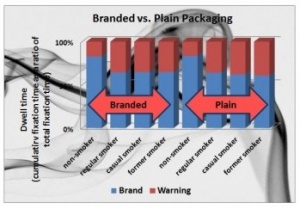

There may be other potentially modifiable factors which may influence alcohol consumption and drinking rate. These might include marketing signals (i.e., branding), and vehicles for these signals such as the glasses from which beverages are consumed. Legislation to control or limit these signals may therefore influence drinking behaviour. A parallel can be drawn with the tobacco control literature, where plain packaging has been shown to increase visual attention towards health warnings compared with branded packaging in non-smokers and light smokers[9]

Australian Court rules that Plain packaging doesn't infringe IP - 15 Aug 2012

In a case where Tobacco companies went to court to argue that plain packaging would infringe on the Intellectual Property, Chief Justice Robert decided that

... a majority of the High Court found the government's legislation did not involve an acquisition of big tobacco's property under the commonwealth constitution.[10]

UK Department of Health public consultation - petitions handed in before deadline Aug 2012

Over 235,000 signed a petition against plain packaging organised by Hands off our Packs.[11]

Over 75,000 signed a petition for plain packaging organised by CRUK.[12]

Roy Ramm, Former Commander of Specialist Operations at New Scotland Yard (Jul 2012)

I've had the privilege of commanding the Scotland Yard's Serious and Organised Crime branch and saw clearly how illicit trade in cigarettes and tobacco goes beyond what some might term mere 'petty criminality'. My former colleagues in Northern Ireland and other international law enforcement agencies identified the proceeds of smuggling as an important source of terrorist funding.

[...]

It would be disastrous if the government, by introducing plain-packaging legislation, removes the simplest mechanism for the ordinary consumer to tell whether their cigarettes are counterfeit or not.

[...]

First, plain packaging will be easier to counterfeit than branded packs. Once you've forged one packet with the name of the product on it, you've forged them all. Secondly, if it is easier to fake the packet, then it will be encouragement for organised crime groups to produce more and more fake tobacco to contain within them.[13]

MPs Open Letter[14] to Secratary of State for Health (Jul 2012)

In July 2012, 50 cross-party Members of Parliament signed an open[14] letter to the Secratary of State for Health (Andrew Lansley) pointing out perceived flaws in Plain Packaging, mentioning

There is no reliable evidence that plain packaging will have any public health benefit; no country in the world has yet to introduce it. However such a measure could have extremely negative consequences elsewhere. This proposal will be a smuggler's charter. Latest estimates from HM Revenue and Customs show that up to 16% of cigarettes and 50% of hand-rolling tobacco in the UK is smuggled [...] standardised packaging [could] make smuggling simpler and exacerbate [lost revenue to HMRC].

... this policy threatens more than 5,500 jobs directly employed by the UK tobacco sector and over 65,000 valued jobs in the associated supply chain.

... we believe products must be afforded certain basic commercial freedoms. The forcible removal of branding would infringe fundamental legal rights, severely damage principles around intellectual property and set a dangerous precedent for the future of commercial free speech. Indeed, if the Department of Health were to introduce standardised packaging for tobacco products, would it also do the same for alcohol, fast food, chocolate and all other products deemed unhealthy for us?

Peter Sheridan, ex-Assistant Chief Constable (Jun 2012)

The fact is, banning cigarette logos might actually make things worse. Plain packets could be a smugglers' charter. I’ve spent most of my working life as a senior police officer in Northern Ireland, where organised crime gangs and terrorist organisations have turned smuggling knock-off fags, jewellery and clothing into a multi-million pound black market business, alongside their prostitution rings and drug running operations.

[...]

...plain packaging will create a bizarre situation - where branded cigarettes are the tobacco products of choice on the black market. If we hand the control of branded goods to criminal gangs, we could actually be aiding them in their illegal trade.[15]

Roger Helmer MEP (May 2012)

Like a disturbing number of other announcements from the government in recent times, [the plain packaging consultation by the UK government] is worrying from a personal liberty perspective.

There is no question that smoking is a bad for your health. I would recommend that anyone who does smoke stops. However, this doesn’t mean I believe it is justifiable that the state should intervene to remove the intellectual property of a company selling a legal product in a misguided attempt to stigmatise a legal activity.

In the same vein, why should the government use our taxes (and, let’s be perfectly clear, smokers pay far more in tax than they cost the NHS, they are in reality net-contributors to the state) to hector, lecture, cajole or coerce millions of adults to induce them to act in a way that the Department of Health deems to be acceptable? The simple answer is that they shouldn’t.

There is no majority consensus behind standardised packaging, despite what we were told by a recent YouGov poll. The poll in question made claims based on a highly leading question and the President of YouGov happens to be on the Board of Trustees of a taxpayer funded anti-smoking lobby organisation, ASH. And even if there was a consensus, government should exist to support individual rights rather than to pander to calls from vested interest groups.[16]

Suzi Gage (May 2012)

Even second year students, trying to work their way round the intricacies of anti-smoking propaganda still slip up:

Yesterday an article in the Daily Mail was brought to my attention by Ben Goldacre, and Transform Drug Policy Foundation. There have been a few articles along a similar line to this one, questioning tobacco control research and policy. This one seemed particularly one-sided, so it's made me decide to go through the arguments, and discuss. The very first sentence of this article riled me, I have to say:

There are few industries to have come under such sustained attack as big tobacco.

It's almost too ridiculous to know where to start. I may be arguing semantics here, but I would say it's not the tobacco industry under attack so much as the disease and death caused by smoking cigarettes.[17]

Having spotted what she perceives to be a semantic argument, she then goes on to make a mistake of her own that begs a similar sort of semantic argument:

So on to the meat. One thing that immediately leaps out to me about this article is that nowhere does it state that tobacco KILLS PEOPLE. OK, we all know this, but it's fundamental as to why there is this legislation in the first place. It's not there as some 'Nanny state' agenda, it's put in place primarily because there is evidence that most (8 out of 10 according to a cancer research document on the subject) people start smoking before the age of 19.[17]

Whoops. That's not what it says at all.

It says that 8 out of 10 smokers start before the age of 19, not 8 out of 10 people. Even using CRUK's own debatable figures, only 21% of the UK population smoked in 2010[18], indicating around 17% of the population started before the age of 19, not the 80% of the population Ms. Gage suggests. Yes, it's a blog post, but as a 2nd year Epidemiology PhD student[19], one would hope for such egregious mistakes which get the numbers almost an order of magnitude wrong to not actually be present. Or at least corrected in a timely fashion - the mistake (published at the beginning of May) was still present over two months later.

Ford (2012)

A Cancer Research UK funded study of 48 Scottish 15-yr-olds which prompted stories of "Tobacco companies are designing cigarette packs to resemble bottles of perfume or with lids that flip open like a lighter to lure young people into smoking"[20] but in fact shows that teenagers are remarkably unaware of current packaging, and thus plain packaging will serve no useful purpose in reducing the likelihood of teenagers taking up smoking.

Borland, Savvas (2012)

An internet survey of only 160 young Australian smokers, for Tobacco Control, were shown different formats of cigarettes differing by shape, patterning of the filter end, and branding concludes, that the format of the cigarettes themselves should be standardised as 'plain' because of the participants' perceptions that branded cigarettes with cork-patterned filters are higher in quality and stronger in taste

London Economics (2012)

The results of surveying 3,000 people on the effects of the removal of various 'product signals' (such as the branding, or other differentiators between brands) on various products (i.e. not just tobacco) suggest that plain packaging would result in customers buying cheaper brands for lack of any other signals to select brands on. This could result in the average price of cigarettes dropping, and tobacco companies further reducing their prices to maintain market share. Furthermore:

"If greater price competition were to occur (and given the importance of price signals in the marketplace), there may be a possible increase in the level of consumption, especially amongst those individuals with fewer financial resources. Other factors held constant, the removal of all packaging imagery and possible subsequent price falls may also encourage younger people to take up smoking in the first instance."

Royal Holloway, University of London project (2012)

While nothing as grand as a 'study' with a published paper such as the University of Bristol study appears to pretend to be, Tim Holmes has been supervising a study by his 3rd year psychology students[1]. In his own words:

To be honest, our initial hypotheses all related to the picture messages and in the best research tradition returned non-significant results! However, we were surprised to observe two interesting results: the non-smokers looked at the warning messages much less than the other participants, and there was no difference between plain and branded package designs in the amount of time spent looking at the warning message. Now, it’s great that the right people are looking more at the warning message, but if this doesn’t result in an increased risk perception then surely the messages aren’t doing their job! Moreover, if removing the brand identity doesn’t change the way people look at the packets then maybe plain packaging, which will be costly to implement, isn’t the best of ideas.

Munafò, Roberts, Bauld & Leonards (2011)

A study, by the University of Bristol, on of the eye movements of 43 (either largely or solely) university-age students when presented with images of both branded and plain packs.

Problems with the study include disparity in the size of packs used between branded and plain packs, and the small number of participants (less than 25 in each of the three cohorts) with a total male/female ratio of 2/1 and what is presumed to be a narrow age range (average age was 23/24.)

A more serious problem with this study is that it reports its results as being an effect of "salience", which if true, affects low-level, bottom-up visual processes and so should produce similar results in ALL participants, whereas they only find a significant effect for non-smokers and weekly smokers (average of about 8 per week) with NO EFFECT for regular smokers.

J Padilla & N Watson (2008)

Commissioned for Phillip Morris International (PMI), by The Law and Economics Consulting Group(LECG) to review previous research on the subject of generic (plain) packaging, largely with regard to teenagers. It concludes that none of those papers reviewed could provide a reliable basis on which to determine if plain packaging would reduce smoking levels.

Department of Health (2008)

Entitled Consultation on the future of tobacco control, aimed at "PCT CEs, NHS Trust CEs, SHA CEs, Foundation Trust CEs, Medical Directors, Directors of PH, Directors of Nursing, Local Authority CEs, Communications Leads," this report came up with a lot of conclusions that contained the words 'may,' 'might,' 'could' and other weasel words.

It was also very selective in quoting parts of other research, while ignoring the parts that contradicted the, perceived, desired outcome for this report.

M Goldberg, et al. (1995)

A report for Health Canada, of teenagers, over 5 different studies, to examine the potential effect plain packaging might have on

- the uptake of smoking to begin with,

- the impact on the recognition of, and the ability to remember, the warnings on packaging,

- the probability of stopping smoking

The surveys were largely about what teenagers think they'd do, and not what they'd actually do, with regard to plain packaging.

References

- ↑ File:Mexico plain packaging.pdf

- ↑ File:Roxon press conference may 2011.pdf

- ↑ http://www.insideretail.com.au/IR/IRNews/Plain-packs-wont-hurt-5693.aspx

- ↑ Selecting the Evidence - Rupert Darwall

- ↑ Australia's plain tobacco packaging - The Lancet

- ↑ Tax rise will cost smokers a packet - Yahoo News

- ↑ Tobacco taxes in Australia - Tobacco in Australia

- ↑ a b Tobacco sales in Australia since plain packaging - IEA

- ↑ Glass Shape Influences Consumption Rate for Alcoholic Beverages - PLoS ONE

- ↑ Big tobacco says plain packs are bad - Sky News

- ↑ Over 235,000 petition against plain packaging - Hands Off Our Packs!

- ↑ More than 75,000 Cancer Research UK supporters want to ban tobacco branding - CRUK

- ↑ Government Plans for Plain Packaging Will Boost Illicit Trade - Huffington Post

- ↑ a b Open Letter (to the Secretary of State for Health) - Scribd

- ↑ Plans for plain packaging of cigarettes are a charter for organised crime and a danger to our children - Daily Mail

- ↑ Plain packaging? Plain nonsense - The Commentator

- ↑ a b Tobacco Control, Plain Packaging, and Media Misinformation - Sifting the Evidence blog on SciLogs WebCite archive

- ↑ Smoking statistics - CRUK

- ↑ Suzi Gage's profile - Nature Network

- ↑ Designer packs being used to lure new generation of smokers - The Independant